Priority 3: Create & maintain strong partnerships with secondary messengers

Checklist to Build Trust, Improve Public Health Communication, and Anticipate Rumors During PHEs

Summary

❏ Activity 1: Create a strategy for maximizing the use of secondary messengers in public health communication efforts

❏ Task 1.1: Conduct an assessment to understand needs of key partners and likely secondary messengers

❏ Task 1.2: Identify and engage with potential strategic partners for secondary messaging

❏ Task 1.3: Identify public health capacities and resources that can be leveraged as benefits to formal secondary messengers❏ Activity 2: Develop formal processes to engage and incorporate secondary messengers into message development, distribution, and evaluation efforts

❏ Task 2.1: Develop shared expectations with potential partners

❏ Task 2.2: Collaborate with partners on message development and distribution efforts❏ Activity 3: Cultivate opportunities for informal sharing of messages

❏ Task 3.1: Leverage informal secondary messengers in virtual spaces

❏ Task 3.2: Leverage informal secondary messengers in physical spaces

Secondary messengers—people and institutions outside of public health departments and government agencies—play important roles in PHEPR by disseminating health messaging, building trust in public health, and dispelling rumors.1 Health departments may create formal partnerships with secondary messengers, such as working with CBOs that support public health message dissemination or conduct face-to-face engagement activities. Formal secondary messaging partners can include people and organizations that have established trust and good rapport with community members. Alternatively, some secondary messengers work informally or independently of health departments, such as when family members share health information in a group chat or when medical experts share health information on social media or other platforms.1

Creating and maintaining partnerships with secondary messengers is an effective way for public health agencies to build social capital and gain trust with the community while addressing gaps in health equity.2,3 Establishing partnerships, either formal or informal, with trusted community influencers and organizations before a PHE allows health agencies to allocate the time, support, and resources to be more proactive with needed health initiatives, build stronger relationships, and establish trust.4-6 In addition to building trust and gaining new perspectives, another benefit of these partnerships is the ability to reach more demographic groups and potentially access hard-to-reach communities.3

Activity 1: Create a strategy for maximizing the use of secondary messengers in public health communication efforts

While many potential partners and secondary messengers may emerge during a health emergency, developing a pre-existing strategy that incorporates the needs of the community, strategic partners, and processes to provide value to both public health and partners can greatly improve engagement efforts. Furthermore, by planning for the inclusion of secondary messengers in public health communications, health departments can improve trust through longer term relationships and engagement with partners. Incorporating flexibility into strategies is key, as each partnership will require discussion and compromise between stakeholders.5,7

Task 1.1: Conduct an assessment to understand needs of key partners and likely secondary messengers

Before establishing partnerships, public health communicators should learn about important health issues in their jurisdiction, who is affected, and the major contributing factors. This information can help in the development of region-specific plans to identify and engage with appropriate community partners that may serve as secondary messengers. There are different approaches to understanding community needs (see Priority 2), which vary in detail, time, and resources required. For example, health departments may conduct their own community health needs assessment or leverage ongoing assessments conducted by regional entities such as local hospitals.5,7

Figure 1. Steps to conducting a community health needs assessment.7

Generally, community health needs assessments should be done cyclically and frequently to identify developing health gaps and policy implications.8,9 Based on the results, public health departments can more easily quantify what is needed from community partners, identify key relationships, and adapt relationships as needs evolve.6,8

Task 1.2: Identify and engage with potential strategic partners for secondary messaging

After collecting information about community needs, public health departments should identify and strengthen connections with potential partners that are well-known and trusted in the community.6 Some potential approaches are described below. Existing free toolkits like NACCHO’s Mobilizing for Action Through Planning & Partnerships 2.0 Handbook (MAPP 2.0) provide in-depth guidance on best practices to identify and engage community stakeholders.6

Table 1. Avenues to discover and connect with formal and informal secondary messengers3,10,11

| Type of partners | Methods for identifying secondary messengers |

|---|---|

| Formal Messengers |

|

| Informal Messengers |

|

| Formal and Informal Messengers |

|

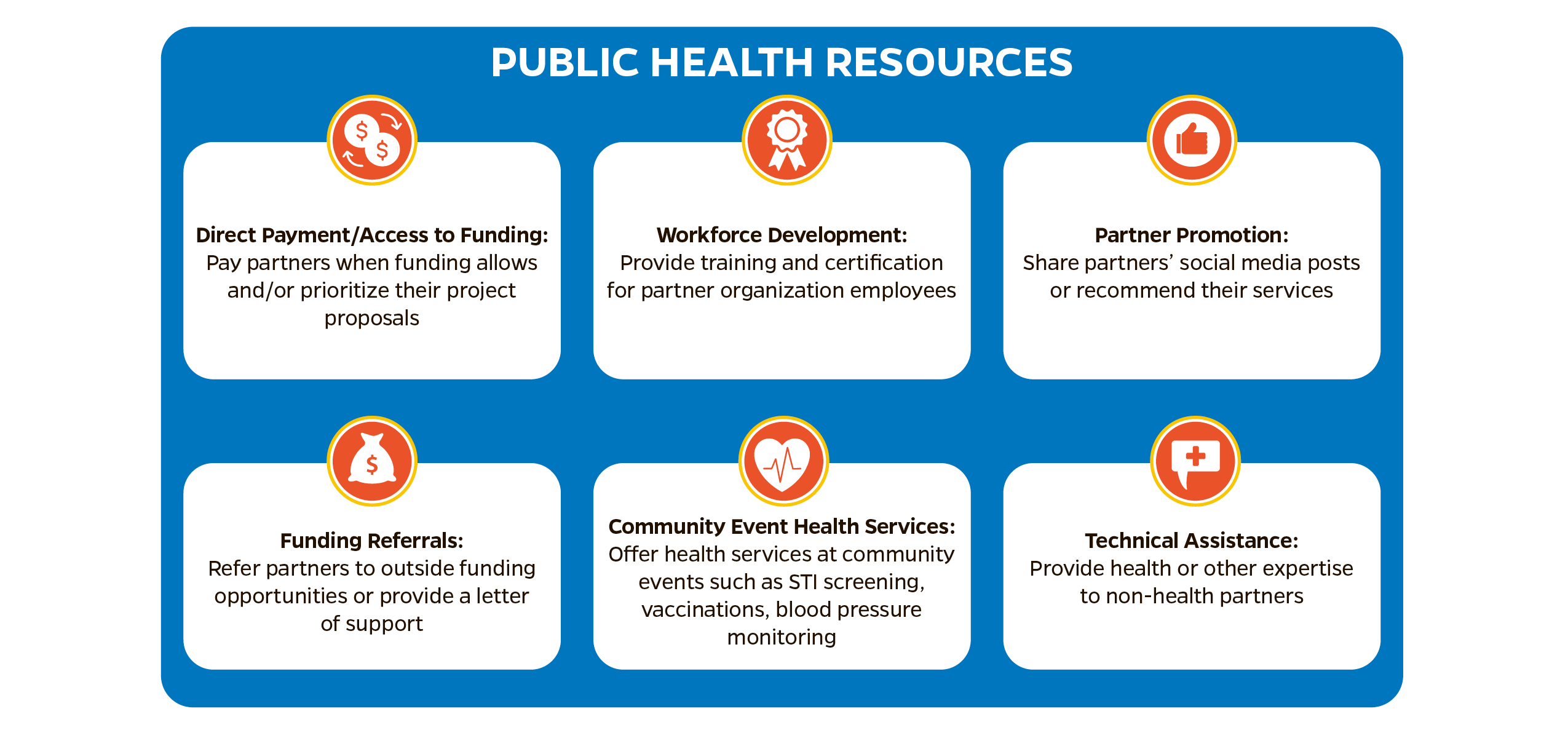

Task 1.3: Identify public health capacities and resources that can be leveraged as benefits to formal secondary messengers

Public health partnerships should be equitable and mutually beneficial to partners. To achieve this, health departments should identify the resources and services they can offer to formal secondary messengers, especially because limited funding may not allow for direct compensation.3,10 Getting input from current or potential partners helps ensure that partnerships make sense and are providing mutual benefits. Public health agencies should regularly check-in with their secondary messaging partners before, during, and after PHEs to verify that partners are benefiting. Some examples of benefits include assistance with non-health emergency initiatives, financial support, health services at events, communication resources, and workforce development assistance.10 Keeping partners informed about guidance changes or emerging issues, as well as the science that supports any policy changes, can also help them support the community.

Figure 2. Examples of public health resources that can be shared as benefits for secondary messengers.3,10,12,13

Activity 2: Develop formal processes to engage and incorporate secondary messengers into message development, distribution, and evaluation efforts

Formal processes that incorporate selected secondary messengers into sustainable, mutually beneficial partnerships can improve public health efforts to enhance communication and trust. These procedures require flexibility and thorough planning and discussion, as each partnership will be different; however, having formalized procedures provides partners with a clear understanding of engagement, onboarding, and needs. Building these relationships before emergencies will strengthen response capabilities and allow more time and effort to build the partnership.5

Task 2.1: Develop shared expectations with potential partners

Health departments should connect with prospective partners to develop mutual expectations and delegate responsibilities. Depending on how potential partners are identified, approaches will vary.14 For example, health departments can provide resources and information about their initiatives to identified partners, outlining goals and reasons for the partnership.7,10 Both public health officials and partners should discuss expectations and strategies for secondary messaging, ensuring each stakeholder’s needs are met to achieve individual and shared goals. Partnership terms should be developed collaboratively and regularly reevaluated to maintain equitable alliances in evolving environments. Health departments should check in frequently and regularly with partners to assess successes and failures, adjust strategies, provide support, identify challenges, and evaluate the overall partnership.5,10,13 Recognizing and acknowledging power differentials and careful planning can cultivate trust and clarify roles between partners.5,6,10

Task 2.2: Collaborate with partners on message development and distribution efforts

Community partners can provide valuable insights, help tailor messages to specific audiences, and reach a broader audience through existing relationships.3,6,9,12,15-17 Collaborating effectively with already trusted community partners can help public health departments bridge gaps in trust.3,6,10 Depending on the partnership and its goals, there are various ways to work with partners on message development and dissemination. This can include identifying and crafting messages for specific audiences, finding and filling gaps in current messaging strategies, sharing messages across partners’ social networks and other platforms, or leveraging existing community relationships to strengthen trust in public health. It is important for health departments to share with partners not only the messages they wish to convey but also the broader rationale behind them, including the department’s role in decision-making. Throughout the message development and delivery process, both partners should continuously evaluate their messaging strategies and develop strategic plans that leverage successes and navigate barriers. See Priority 5 for further guidance on message development, tailoring, and evaluation.

The following table shares examples of partnerships, outlining what partners shared and how they benefited.

Table 2. Real examples of public health partnerships

| Example | Benefit to public health | Benefit to partner |

|---|---|---|

| The Academic Public Health Corps (APHC) partnered with the Association of Islamic Charitable Projects Massachusetts (AICP) on a COVID-19 Vaccine Equity Initiative through a competitive grant process.13 | AICP revealed to APHC the need for more culturally representative informational materials. AICP provided guidance on how best to execute the development and dissemination of the materials, including distributing the finalized materials at their events.13 | APHC held an informational webinar for AICP audiences on COVID-19 and vaccination with live Arabic translation. A recording was made available to those unable to attend. APHC also held a Q&A session during which community members could discuss cultural concerns that were not addressed in public health messaging.13 |

| The Hawai’i Public Health Institute (HIPHI) ran a competitive grant program to support local CBOs’ COVID-19 outreach programs. Partners in Development Foundation (PIDF), a nonprofit supporting underserved and hard-to-reach communities in Hawai’i, won one of these CBO grants to implement 2 projects.18 | PIDF leveraged their network of community partners to distribute more than 70,000 COVID test kits and personal protective equipment to rural island communities that HIPHI may not have been able to reach otherwise. Additionally, PIDF facilitated Global Biorisk Advisory Council training covering infectious disease mitigation strategies and proper disinfection processes for more than 400 individuals.18 | HIPHI provided necessary funding support to PIDF’s program development and distribution efforts, allowing them to better serve their community and meet their unmet public health needs.18 |

Partners may also assist in increasing social media engagement, including by offering valuable insights about community behavior and highly trafficked sites and platforms. Public health agencies can use this information to cultivate a stronger social media presence with higher potential for engaging informal secondary messengers. Additionally, promoting public health messages and social media posts on partner platforms can increase visibility and encourage sharing.19

Activity 3: Cultivate opportunities for informal sharing of messages

Informal secondary messengers are individuals, groups, or organizations that share health information without any formal agreement with public health agencies. This approach is a cost-efficient and effective way to distribute impactful information via social media platforms or physical materials. Examples of informal secondary messaging include posting health department memes in group chats or sharing health department posts on social media or in-person. This approach helps public health departments or other government agencies reach social networks and their community members who might not be reached by formal partnerships.1

Task 3.1: Leverage informal secondary messengers in virtual spaces

Social media platforms can be a high-impact and low-effort tool for increasing public health messaging visibility. Posting shareable infographics on public health social media pages is an easy way to build an audience and increase message amplification. In some cases, however, limited attention is focused on public health-sponsored pages. In these cases, identifying other virtual spaces frequented by intended audiences is critical. Monitoring and participating in social media trends, when appropriate, is another way public health departments can increase engagement and gain larger audiences.19 See Priority 5 for guidance on developing impactful social media messaging.

Health departments should keep in mind that messages may be shared in their original format or altered. Therefore, it is important that key public health ideas are clear and prominent to retain accuracy. Be cautious of the potential for distorted messaging or the loss of important context during sharing.

Task 3.2: Leverage informal secondary messengers in physical spaces

Another way of leveraging informal partnerships is in physical spaces. Public health departments can participate in community events, distribute informational materials in community spaces, and engage in other activities that provide audiences with relevant and up-to-date health information. Participants can take this information home or to other events and distribute it to other audiences. For example, school-aged children who speak a different language at home might learn about health topics at school and tell their families about the information.1

Public health employees engaging in dialogue at events can build trust, which can help public health messages spread through word of mouth.7 Increasing face-to-face time with community members increases the likelihood that they will spread public health messaging to their families, workplaces, or social circles. Public health departments should take these opportunities to share information, answer questions, and encourage continued dialogue.

In addition to attending events, public health employees can, with permission, leave health-related materials in community gathering spaces like the YMCA, public restrooms, local barbershops, churches, schools, etc., for passive distribution. Customizing materials, with support from formal partners, to match community demographics and cultures can help more people see and understand such resources. See Priority 5 for more on developing materials.

Priority 3 References

References

- Potter CM, Grégoire V, Nagar A, et al. A practitioner-focused checklist to build trust, address misinformation and improve risk communication for public health emergencies. [Manuscript submitted for publication.]

- Schoch-Spana M, Brunson E, Chandler H, Gronvall GK, Ravi S, Sell TK, Shearer MP. Recommendations on How to Manage Anticipated Communication Dilemmas Involving Medical Countermeasures in an Emergency. Public Health Rep. May 30, 2018. doi:10.1177/0033354918773069

- Turin TC, Chowdhury N, Haque S, Rumana N, Rahman N, Lasker MAA. Meaningful and deep community engagement efforts for pragmatic research and beyond: engaging with an immigrant/racialised community on equitable access to care. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(8): e006370.

- Public Health Institute Center for Wellness and Nutrition. We’re All in This Together: Strengthening Community Engagement Strategies Through a Collaborative Technical Assistance Model. Sacramento, CA: Center for Wellness and Nutrition; 2022.

- McNeish R, Rigg KK, Tran Q, Hodges S. Community-based behavioral health interventions: Developing strong community partnerships. Eval Program Plann. December 10, 2018. doi:0.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.12.005

- National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). Mobilizing for Action Through Planning & Partnerships: MAPP 2.0 User’s Handbook. Washington, DC: NACCHO; 2023. https://www.naccho.org/programs/public-health-infrastructure/performance-improvement/community-health-assessment/mapp

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Public Health Assessment Guidance Manual: Community Engagement Actions, Tools, and Activities. Reviewed April 14, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pha-guidance/engaging_the_community/community_engagement_tools_actions.html

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Community Needs Assessment. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fetp/training_modules/15/community-needs_pw_final_9252013.pdf. Original source removed. Related source: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/24069

- O’Donnell E. Seven Steps for Conducting a Successful Needs Assessment. National Institute for Children’s Health Quality. Undated. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://nichq.org/insight/seven-steps-conducting-successful-needs-assessment. Original source removed but available at https://www.everybodytexas.org/uploads/files/general/Seven-Steps-for-Conducting-a-Successful-Needs-Assessment.pdf

- National Business Coalition on Health, Community Coalitions Health Institute. Community Health Partnerships: Tools and Information for Development and Support. March 4, 2013. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/media/document/Community_Health_Partnerships_tools.pdf

- Huisman M, Biltereyst D, Joye S. Sharing is caring: the everyday informal exchange of health information among adults aged fifty and over. Information Research. March 2020. https://informationr.net/ir/25-1/paper848.html

- Association of American Medical Colleges Center for Health Justice. Local Partnerships Are Key to Building Community Trust. Published April 27, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.aamchealthjustice.org/news/news/local-partnerships-key

- Yasmin S, Haque R, Kadambaya K, Maliha M, Sheikh M. Exploring How Public Health Partnerships with Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) can be Leveraged for Health Promotion and Community Health. Inquiry. November 30, 2022. doi:10.1177/00469580221139372

- Michener JL, Castrucci BC, Bradley DW, Hunter EL, Thomas CW, Patterson C, Corcoran E, eds. The Practical Playbook II: Building Multisector Partnerships That Work. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2019.

- Vaccinate Your Family. SQuaring Up Against Disease (SQUAD) pamphlet. Undated. https://vaccinateyourfamily.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/SQUAD-1-PG-2023-V2.pdf

- Angelo, J. Vaccination and Food Resources to Nearly 200 Micronesians. Living Islands. Published March 13, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://livingislands.org/vac313/

- CDC Foundation, Vaccine Equity Cooperative, Health Leads. Leveraging Immunization Manager and Community Based Organization Partnerships for COVID-19 and Beyond. CDC Foundation, Vaccine Equity Cooperative, Health Leads webinar. February 24, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://vaccineequitycooperative.org/resource/leveraging-immunization-manager-and-community-based-organization-partnerships-for-covid-19-and-beyond-recording/

- Hawai’i Public Health Institute. CBO Grant Highlight: PIDF and MCOH Complete their COVID-19 Projects. Published June 26, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.hiphi.org/cbo-grant-highlight-pidf-and-mcoh-complete-their-covid-19-projects/. Original source removed.

- Miller MR, Snook WD, Walsh E. Social Media in Public Health: A Vital Component of Community Engagement. de Beaumont Foundation. Published November 25, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://debeaumont.org/news/2019/social-media-in-public-health-a-vital-component-of-community-engagement/