Priority 2: Develop meaningful & lasting relationships with your community

Checklist to Build Trust, Improve Public Health Communication, and Anticipate Rumors During PHEs

Summary

❏ Activity 1: Establish public health personnel as trusted members of the community

❏ Task 1.1: Assess readiness for community relationships

❏ Task 1.2: Identify key principles and norms for engaging with communities

❏ Task 1.3: Be immersed in community spaces and present at local events, initiatives, and meetings

❏ Task 1.4: Build in mechanisms for sharing decision-making processes with communities❏ Activity 2: Make strategic and intentional investments in building community

❏ Task 2.1: Conduct assessments to understand community networks and needs to inform a plan of action

❏ Task 2.2: Establish a track record of supporting the community in a range of ways, even if small

❏ Task 2.3: Develop avenues for community members to integrate into the local public health community

❏ Task 2.4: Prioritize sustainability when building community relationships and evaluate progress

All actors in a community, from health departments to the people they serve, have visions of what a healthy population looks like. These visions may or may not align. Public health personnel can struggle to integrate their communities’ visions when planning, implementing, and evaluating PHEPR programming, which can result in a lack of public trust or buy-in.1 Therefore, building and strengthening relationships between public health departments and the communities they serve is a vital step in increasing trust in public health. Transparency, accountability, and inclusive decision-making with community members is foundational to public health.2

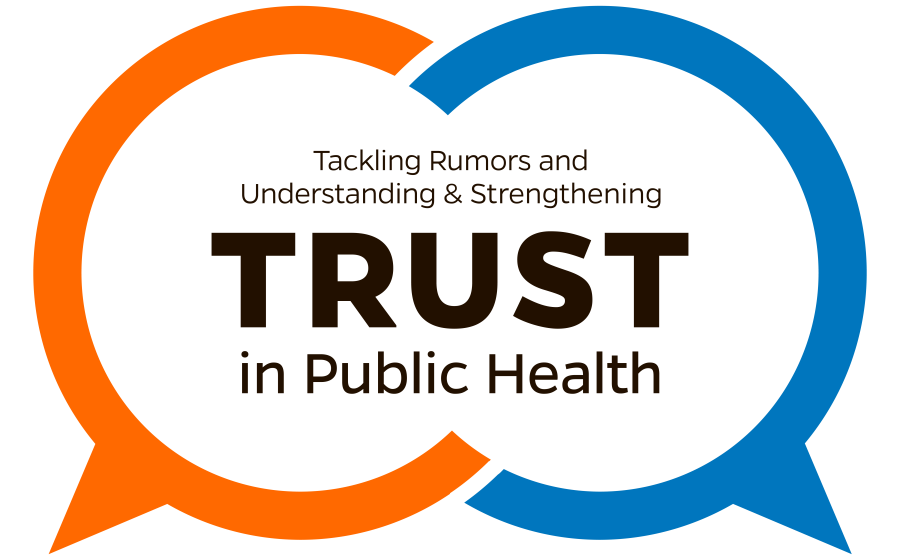

To build trust in PHEPR, public health personnel should establish themselves as trustworthy members of their community and make strategic investments in building community. Approaches can range from basic outreach about public health issues to more sustainable and equitable strategies that involve a higher level of public engagement, empowerment, and shared decision-making, as shown in Figure 1.3-5

Figure 1. This community engagement spectrum illustrates the continuum of public engagement in a participatory process, from low to high levels of engagement (adapted from the International Association for Public Participation5 for the Center for Wellness and Nutrition’s Community Engagement Toolkit3).

Activity 1: Establish public health personnel as trusted members of the community

As mentioned in Priority 1, communities’ historical experiences influence their trust in public health organizations. Because of these previous encounters, some communities are not always quick to trust guidance from public health departments, healthcare institutions, researchers, or government health officials.6 In order to dispel what could be harmful narratives, public health departments must build authentic, honest, transparent, and consistent relationships with community members to establish themselves as trustworthy. This relationship building helps public health departments and other health officials carry out important programming in their communities and respond to local public health issues, especially during PHEs.

Task 1.1: Assess readiness for community relationships

Building relationships requires time and dedicated resources, which public health departments and other health officials may lack or prioritize elsewhere in the face of other pressing needs. Public health agencies should conduct an internal assessment3,7 to understand whether they have sufficient organizational buy-in, sustainable interest, and resources to build constructive relationships and partnerships with communities. They should reflect on questions like:

- With which communities do you want to build relationships?

- Does your health department perceive community involvement as a priority in identifying community health issues?

- Does your health department have a champion(s) or leader(s) who will drive efforts to build and sustain relationships?

- What does your health department want to accomplish by developing relationships with the community?

- How positive are existing collaborations with the community?

- How involved do you want community members to be in health department activities?

- What types of community involvement can your health department accommodate?

- How flexible can your agency be when building relationships with communities?

- What can you contribute to communities?

- Are you prepared to cede, transfer, or share decision-making processes with the community?

- How do your answers to these questions change before, during, and after PHEs?

- Are resources, staffing, and organizational interest sustainable?

If, upon reflection, public health leaders determine they are not ready to build relationships with communities, it would be prudent to focus on building internal readiness, using strategies with lower levels of public involvement, or identifying which relationships might be feasible to pursue in the future.

Task 1.2: Identify key principles and norms for engaging with communities

Public health officials can bolster their trustworthiness in communities by embodying the values that their communities find important. When developing relationship-building strategies, public health leaders should identify key principles that underpin their approach to community engagement. An agreed set of internal guiding principles can standardize approaches and ensure they are all aligned with community-centered values, such as:

- Transparency. Transparency and openness from public health officials—such as providing timely information about risks, clarifying the science behind public health guidance, explaining decision-making processes, and claiming accountability—are important trust-building strategies during health emergencies, especially when government-mandated PHEPR measures are socially disruptive and likely to provoke strong emotional responses.8-11,20

- Flexibility. Relationships should evolve based on the real-time needs of different communities, including their priorities and goals.6 If public health officials are willing to change and adapt their plans to fit a community’s needs, the community will view them as more reliable, accessible, and trustworthy.

- Equity. Understanding and accounting for structural inequities and social injustices helps public health personnel build more accessible, intentional, and supportive relationships with diverse communities, especially when there are power imbalances between public health authorities and community members.6 Participatory approaches like community-based participatory research, participatory budgeting, and participatory action research are effective in building mutually beneficial relationships.4,12,13

- Mutual respect. Showing mutual trust and respect for partners, as well as their knowledge, expertise, and voice, is crucial for successful community-based participatory partnerships.6,7 An absence of mutual respect and co-learning can result in a loss of trust, time, and resources.4

- Honesty. When building relationships with communities, public health departments must communicate openly and honestly or risk being perceived as opportunistic and deceptive.7 This includes taking responsibility for mistakes and disclosing conflicts of interest. Violating this principle may trigger possibly harmful narratives rooted in distrust of authorities and conspiracies.14

Public health personnel can use these principles, as well as any other values relevant to their mission, to establish norms and set expectations about how they intend to work with communities. They should be clear about the goals of their engagement efforts; make a case for why a relationship is worthwhile for all parties involved; put in the work to learn about their community's culture, social networks, political and power structures, norms, and values; and (perhaps most importantly) keep their promises after setting these expectations.7,15

Two examples that illustrate both key principles in action and how to effectively work with communities to establish these principles include:

- The National Association of County and City Health Officials’ (NACCHO) Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships 2.0 Handbook (MAPP 2.0), which outlines foundational principles that were developed in collaboration with communities and embedded into the MAPP Theory of Change to ensure engagement efforts are community-driven.6

- The US government-funded Principles for Community Engagement, which details 9 actionable and specific key principles that guide the formation, implementation, and sustainability of engagement efforts, developed with input from a community task force.4

Task 1.3: Be immersed in community spaces and present at local events, initiatives, and meetings

Public health personnel should establish both an active and passive presence in community spaces to be more accessible for, visible to, and connected with community members. Showing a presence can help lead to authentic development and retention of community-based relationships. It is important to note that many traditional community participation and engagement efforts often use a top-down approach that does not prioritize the community’s needs and drives unequal distributions of power. This can perpetuate distrust of public health and government officials. To build trust, public health practitioners should practice respectful and intentional listening and engage with communities more actively.16,17 Public health leaders, practitioners, and staff can:

- Network informally at in-person community events, initiatives, and meetings, and/or attend them as a formal representative to contribute a public health perspective or public health resources.12 For example, when YMCAs host Healthy Kids Days, local health departments can provide public health information and materials at the event, promote the event on social media platforms, and continue the conversation through health education and programming.18

- Participate in virtual discussions and events and create an online presence by posting consistently, intentionally, and meaningfully on social media platforms and websites. Priority 5 details how public health departments can communicate more effectively about PHEPR issues, especially online.

- Meet communities where they are by showing up at events that do not have an explicit health focus.19,20 For example, academic partners who work with the Apsáalooke (Crow Indian) Nation as part of the Messengers for Health project regularly spend time at the reservation and attend social and cultural events.21 Public health officials should make authentic personal connections: ask people questions, tell people about themselves, and go where the people are.22

- Participate in community conversations and conduct outreach even when people are initially unwelcoming or harbor deep distrust of public health.22

- Contribute logistical planning resources as a convenor and bring together diverse community organizations, coalitions, task forces, stakeholders, and members over shared dialogue.7

- Build relationships with community members at “third places” or neutral locations (like salons) where people spend time, socialize, exchange ideas, and enjoy themselves outside of their homes or workplaces.23 These locations play an important role in cultivating a strong sense of community, and they can provide a space for public health to engage with the community.

- Remain accessible to and build relationships with local media outlets, as community members often rely on news to stay informed about health issues.9,24

By being present, public health personnel show they are actively part of their community, interested in connecting, and see themselves as one with the community. While networking with specific populations, leaders, and community members is important, public health practitioners benefit from immersing themselves in the social fabric of their community to avoid these interactions being viewed as a transactional process.3 Additionally, after meeting people and making connections, public health staff should retain these relationships by making it as easy as possible for community members to stay engaged. Examples of this might include providing childcare at public health convenings, facilitating transportation to public health events, meeting where communities feel comfortable, providing incentives, and more. Priority 4 explores how public health staff can pursue more formal listening and feedback gathering mechanisms for PHEPR purposes.

Task 1.4: Build in mechanisms for sharing decision-making processes with communities

There is often an imbalance of power between public health departments and the communities they serve, which can make communities skeptical about the intentions behind PHEPR activities. Public health officials should empower communities to set public health agendas, shift public health discourse, and make decisions about their community’s health.25 When public health fosters a “together we can” culture, it becomes a more trustworthy collaborator.12 Public participation can enhance the legitimacy, transparency, and justice of decision making and improve trust in public institutions.2 However, this means that public health officials must be prepared to release control of some actions and outcomes to the community.15 They can pursue the following approaches for sharing decision making when developing community relationships:

- Demonstrate willingness to listen and be guided by communities’ needs, interests, and voices.26

- Be open to unanticipated ideas and be receptive to nontraditional community relationships.2

- Identify strategic opportunities for communities to share their expertise and knowledge.26

- Practice two-way communication with the public to stay informed and engaged in dialogue and exchange (ie, going beyond one-way mass messaging, such as public services announcements or social media campaigns).2

- Connect with communities to help them gain more control over factors that affect their health.26

- Use participatory approaches to collaboratively define public health problems and solutions.2

- Actively respond to issues the community feels are important and empower community groups to engage in open dialogue with government entities.2

Activity 2: Make strategic and intentional investments in building community

Public health employees can convey that they are sincere, intentional, and thoughtful about building community relationships by making proactive, strategic investments. Public health staff and communities should work to understand how they can support each other not only by providing information, resources, or incentives but also through collaborative ways of interacting, acting, and recovering from public health events. By investing in communities, public health departments show with action—not only words—that they care about the communities they serve, which bolsters public trust in them.

Task 2.1: Conduct assessments to understand community networks and needs to inform a plan of action

Health departments and local public health leaders need to understand the formal and informal connections within their communities, as well as the strengths, weaknesses, gaps, and power dynamics of these networks. Stakeholder mapping and analysis activities can help build strategic relationships with communities and formalize partnerships with local leaders, as explored in Priority 3. Additionally, health departments can conduct needs assessments to help understand key health issues in the community. Engaging in these activities can help prepare for PHEs by enhancing understanding of community needs during and after crises, effectively leveraging relationships, and adapting communication strategies.24

Needs assessment methods vary widely across the US, despite the presence of federal and state standards for such assessments.27 Comprehensive community needs assessments include CDC’s Community Needs Assessment,28 the American Hospital Association’s Community Health Assessment Toolkit,29 NACCHO’s MAPP 2.0 Handbook,6 and the Center for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas’ Community Tool Box.30 During emergencies, public health employees can use formative research methods or rapid analysis tools like the CDC’s Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response Toolkit.31 These toolkits include extensive guidance on how to integrate community-based relationship-building as both a precursor to and an outcome of needs assessments. If public health officials are interested in pursuing a more transformative approach to assessing needs, they should:

- Engage, empower, and train community members to design and conduct assessments, as well as to understand and socialize their findings.2 One way to do this is to form an advisory committee that includes people from the community and with varied backgrounds to guide the assessment process.29

- Use mixed-methods approaches and community-based participatory research methodologies throughout the assessment process.4,7,29

- Foster diverse, multisectoral, and proactive relationships with community groups to strengthen shared ownership and decision-making.32

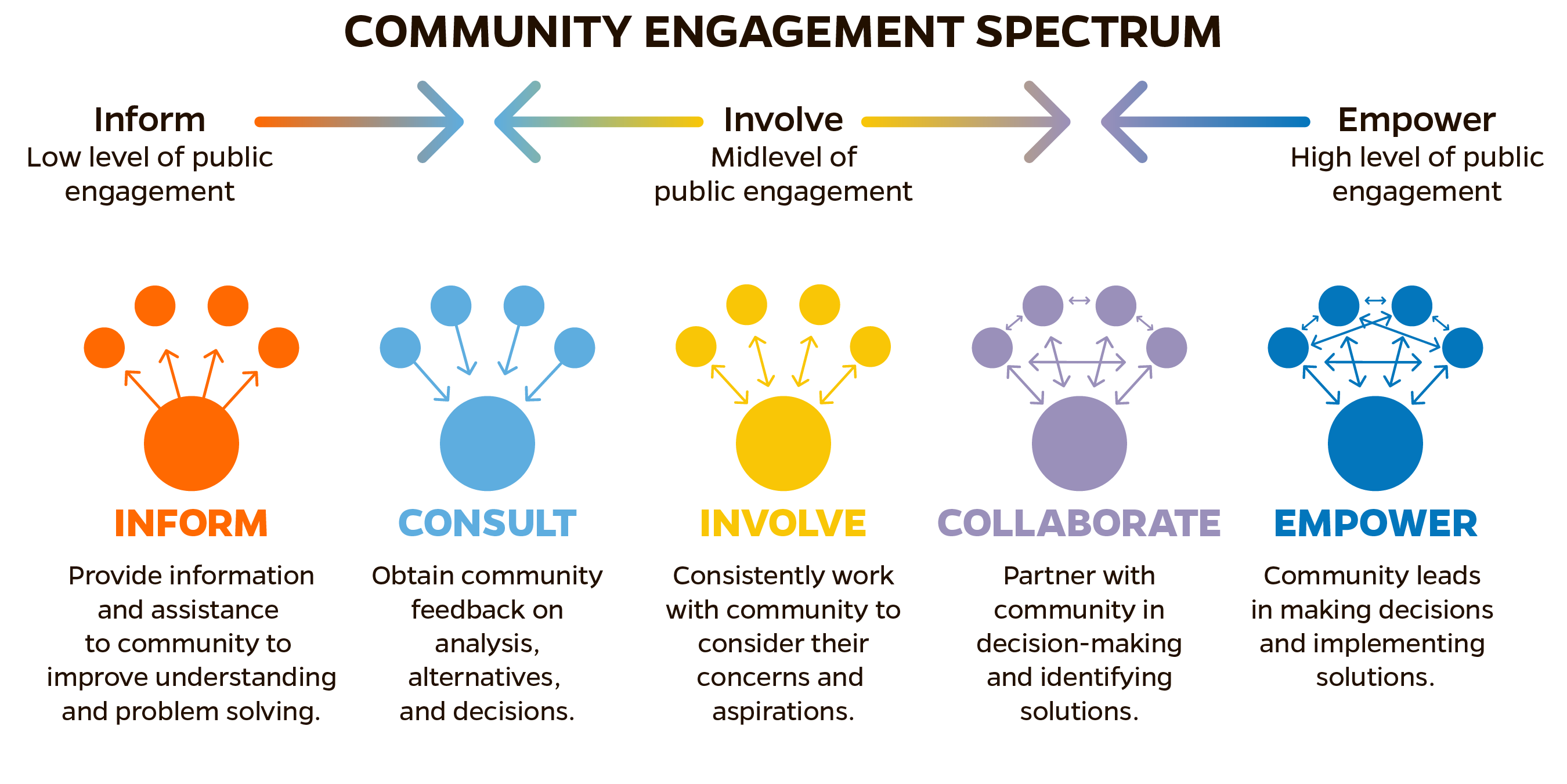

Findings from needs assessments should inform an operationalized strategic action plan. Learnings from community health assessment activities and the community health improvement process are often used to create community health improvement plans (CHIPs). Health departments and related government entities often use CHIPs to set public health priorities and coordinate resources with community partners.4,32 Public health officials can also use findings from assessments to devise an internal community engagement process, such as the Center for Wellness and Nutrition’s process shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. 4-step community engagement process, modified from the Center for Wellness and Nutrition.3

Task 2.2: Establish a track record of supporting the community in a range of ways, even if small

Public health departments are limited in the investments they can make in a community because of funding and scope constraints. Although they may not be able to invest in ways that meet all their community’s needs (eg, funding long-term, large-scale programs and establishing integrated local health systems), they can show up in small ways. For example, health departments can:

- Regularly provide community members with information about public health issues through educational campaigns, topic-specific trainings, awareness activities, and other efforts to improve overall health and science literacy, particularly when faced with a public health issue. Because rumors often fills gaps in knowledge, proactively providing useful and reliable information helps public health departments establish themselves as a visible, accessible, and trusted sources of information and improve communities’ resilience to misleading claims.14,20 See Priority 4 for more on anticipating misleading rumors.

- When possible, provide food, childcare, activities for children, incentives, and other supportive services during public health programs, meetings, and convenings.3 By doing so, public health officials show they are aware of barriers to community participation and are working to remove them. Such efforts can make community members more receptive to relationship-building.

- Advocate for communities by pushing for policy-level solutions to community members’ health-related concerns.33 Public health authorities often serve as mediators among communities, the government, and healthcare systems; by escalating community concerns into policy spaces, public health officials show they are willing to leverage their influence in support of their community. Resources like the NACCHO Advocacy Toolkit provide guidance on how public health officials can advocate for and with the communities they serve.34

Being accessible, consistent, helpful, and dependable, and working in the best interests of the community, creates a strong foundation for community-based relationships to form naturally.

Task 2.3: Develop avenues for community members to integrate into the local public health community

Just as public health employees should meet communities where they are and invest in their goals, they can also create avenues for community members to serve as collaborators, partners, and advocates. Public health departments can use the following approaches:

- Recruit community members into the public health workforce. Public health officials can create pathways, opportunities, and enabling environments for community members to serve as community health workers, public health practitioners, health communicators, emergency response workers, and other staff roles.25 When interest in community health increases during public health events, health department officials should invite community members to engage as volunteers, consultants, and experts. Even if health departments cannot provide funding or opportunities to train and hire a community-based public health workforce, they can connect community members to other resources, trainings, and opportunities.

- Co-create programs and strategies with multisectoral community members. Public health departments should recruit and retain community members and CBOs as thought partners, decision-makers, and implementers. They can convene coalitions, task forces, advisory groups, and other mechanisms to bring diverse community members together and co-create public health solutions, using tools like community visioning, coalition-building, and co-creation workshops.6,35,36 Community-based partners can leverage their deep knowledge of the community and established trust to bring more people into contact with public health.37 Public health departments should make sure to build bilateral and multilateral partnerships with all stakeholders—not only health-related ones—that invest in creating a thriving future for health and wellbeing.38

- Implement integrated PHEPR activities with shared public health and community-based objectives. During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health officials, primary care providers, and CBOs mobilized quickly and effectively to implement testing, vaccination campaigns, and other response activities for community members.37 Public health departments and organizations with shared community health and wellbeing objectives should intentionally connect with each other prior to emergencies to establish mechanisms that enable integration of services. Public health officials and their partners should build off each other’s technical capacities, and, if appropriate, reduce operational constraints. Removing or streamlining barriers like rigid contracts or memorandums of understanding, time-consuming reporting requirements, non-negotiable terms, and requests for free labor will increase the likelihood of sustained relationships.39

Task 2.4: Prioritize sustainability when building community relationships and evaluate progress

To build sustainable, trustworthy, mutually beneficial long-term relationships with communities, public health officials should invest in evaluating progress to understand how partnerships, social networks, community priorities, and inter-collaborator dynamics evolve over time. The following table includes best practices to sustain and evaluate relationships:

Table 1. Sustaining Relationships and Evaluating Progress: Do’s and Dont's

| Do | Don’t | |

|---|---|---|

| Sustaining Relationships |

|

|

| Evaluating Progress |

|

|

Priority 2 References

References

- de Guia S, Novais AP. Community Trust And Relationships: The Key For Strengthening Public Health Systems. Health Affairs Forefront. Published February 28, 2023. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/community-trust-and-relationships-key-strengthening-public-health-systems

- American Public Health Association. Public Health Code of Ethics. Washington, DC: APHA; 2019. https://www.apha.org/getcontentasset/43d5fdee-4ccd-427d-90db-b1d585c880b0/7ca0dc9d-611d-46e2-9fd3-26a4c03ddcbb/code_of_ethics.pdf

- Center for Wellness & Nutrition. Community Engagement Toolkit: A Participatory Action Approach Towards Health Equity and Justice. Center for Wellness & Nutrition/Public Health Institute; 2020. https://centerforwellnessandnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/FINAL-COMMUNITY-ENGAGEMENT-TOOLKIT_-Upd2282020.pdf

- Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Consortium’s Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Principles of Community Engagement (Second Edition). National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11699

- International Association for Public Participation. IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation. Published November 2018. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf

- National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). MAPP 2.0 Handbook. NACCHO; 2023. https://toolbox.naccho.org/pages/tool-view.html?id=6012

- Giachello A. Making Community Partnerships Work: A Toolkit. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes Foundation; 2007. https://aapcho.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Giachello-MakingCommunityPartnershipsWorkToolkit.pdf

- Wilson AM, Withall E, Coveney J, et al. A model for (re)building consumer trust in the food system. Health Promot Int. 2017;32(6):988-1000. doi:10.1093/heapro/daw024

- Henderson J, Ward PR, Tonkin E, et al. Developing and Maintaining Public Trust During and Post-COVID-19: Can We Apply a Model Developed for Responding to Food Scares? Front Public Health. July 13, 2020. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00369

- Hall K, Wolf M. Whose crisis? Pandemic flu, “communication disasters” and the struggle for hegemony. Health (London). November 20, 2019. doi:10.1177/1363459319886112

- Vaughan E, Tinker T. Effective health risk communication about pandemic influenza for vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S324-332. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.162537

- Center for Public Health Practice & Research, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health at Georgia Southern University, Cobb and Douglas Public Health. Health Departments and Authentic Community Engagement. Center for Public Health Practice & Research; 2020. https://phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/4.30.20.Georgia-Southern.Health-Departments-and-Authentic-Community-Engagement-002.pdf

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011.

- Nagar A, Huhn N, Sell TK. Summary Report for Task 8: Identify and Analyze Health-Related Rumors. Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, CDC; 2023.

- Center for Public Health Practice. Building community relationships. Minnesota Department of Health. Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/resources/chsadmin/community-relationships.html

- Gautier L, Sieleunou I, Kalolo A. Deconstructing the notion of “global health research partnerships” across Northern and African contexts. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(Suppl 1):49. doi:10.1186/s12910-018-0280-7

- Hickey G, Porter K, Tembo D, et al. What Does “Good” Community and Public Engagement Look Like? Developing Relationships With Community Members in Global Health Research. Front Public Health. January 27, 2022. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.776940

- Bremerton Family YMCA. Bremerton Family YMCA Facebook Post. Published May 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2023. https://www.facebook.com/plugins/post.php?href=https://www.facebook.com/bremertonymca/posts/pfbid0qivAgNa2v5fN1B6RRnwtQ1cs6jYoRvU1Wma2HidiK74nxK1yKTANZutMRYRTJfR3l

- Joszt L. Strong Community Relationships Key to Improving Health, Said Speakers at National Public Health Week Forum. AJMC. Published April 3, 2018. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.ajmc.com/view/strong-community-relationships-key-to-improving-health-said-speakers-at-national-public-health-week-forum

- Potter CM, Grégoire V, Nagar A, et al. A practitioner-focused checklist to build trust, address misinformation and improve risk communication for public health emergencies. [Manuscript submitted for publication.]

- Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AKHG, Young S. Building and Maintaining Trust in a Community-Based Participatory Research Partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1398-1406. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757

- Center for Community Health, University of Kansas. Chapter 14. Core Functions in Leadership | Section 7. Building and Sustaining Relationships. Community Tool Box. Undated. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/leadership/leadership-functions/build-sustain-relationships/main

- Butler SM, Diaz C. “Third places” as community builders. Brookings. Published September 14, 2016. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/third-places-as-community-builders/

- Schoch-Spana M, Brunson E, Chandler H, et al. Recommendations on How to Manage Anticipated Communication Dilemmas Involving Medical Countermeasures in an Emergency. Public Health Rep. May 30, 2018. doi:10.1177/0033354918773069

- The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a National Public Health System. Meeting America’s Public Health Challenge: Recommendations for Building a National Public Health System That Addresses Ongoing and Future Health Crises, Advances Equity, and Earns Trust. Commonwealth Fund; 2022. doi:10.26099/snjc-bb40

- Human Impact Partners. Strategic Practices Overview. HealthEquityGuide.org. Updated January 25, 2025. Accessed May 15, 2025. https://healthequityguide.org/strategic-practices-overview/

- Ravaghi H, Guisset AL, Elfeky S, et al. A scoping review of community health needs and assets assessment: concepts, rationale, tools and uses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):44. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08983-3

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Needs Assessment: Participant Workbook. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fetp/training_modules/15/community-needs_pw_final_9252013.pdf. Original source removed. Related source: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/24069

- AHA Community Health Improvement. Community Health Assessment Toolkit. Published 2023. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.healthycommunities.org/resources/community-health-assessment-toolkit

- Center for Community Health, University of Kansas. Chapter 2. Assessing Community Needs and Resources Toolkit. Community Tool Box. Undated. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/assessing-community-needs-and-resources

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER) Toolkit: 3rd Edition. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/casper/media/pdfs/casper_toolkit.pdf?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/casper/docs/CASPER-toolkit-3_508.pdf

- Rosenbaum SJ. Principles to Consider for the Implementation of a Community Health Needs Assessment Process. Washington, DC: George Washington University; 2013. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_policy_facpubs/863

- Shah U. Public Health Advocacy: Informing Lawmakers about What Matters Most in Our Communities. NACCHO Voice blog. Published February 5, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.naccho.org/blog/articles/public-health-advocacy-informing-lawmakers-about-what-matters-most-in-our-communities

- National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). NACCHO Advocacy Toolkit. Washington, DC: NACCHO; 2017. https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/2018-gov-advocacy-toolkit.pdf

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Co-Creation: An Interactive Guide. Washington, DC: USAID; 2022. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/Co-Creation_Toolkit_Interactive_Guide_-_March_2022_1.pdf. Original source removed.

- Center for Community Health, University of Kansas. Chapter 5. Choosing Strategies to Promote Community Health and Development | Section 5. Coalition Building. Community Tool Box. Undated. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/promotion-strategies/start-a-coaltion/main

- Veenema TG, Toner E, Waldhorn R, et al. Integrating Primary Care and Public Health to Save Lives and Improve Practice During Public Health Crises: Lessons from COVID-19. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; 2021. https://centerforhealthsecurity.org/sites/default/files/2023-02/211214-primaryhealthcare-publichealthcovidreport.pdf

- The Rippel Foundation. Vital Conditions for Health and Well-Being. Undated. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://rippel.org/vital-conditions-for-health-and-well-being/

- American Public Health Association, Science and Community Action Network. Building Trust-Based Community Partnerships for Public Health Professionals. Webinar. July 27, 2023. https://www.pathlms.com/health/courses/55332