Priority 5: Formulate key message components & maximize message engagement

Checklist to Build Trust, Improve Public Health Communication, and Anticipate Rumors During PHEs

Summary

❏ Activity 1: Draft key messages

❏ Task 1.1: Embrace a basic content format for communicating accurate information in an emergency

❏ Task 1.2: Employ specialized approaches to confront rumors

❏ Task 1.3: Consider and apply lessons from existing messaging models❏ Activity 2: Tailor messages based on understanding of the intended audience

❏ Task 2.1: Identify intended audiences for messaging

❏ Task 2.2: Consider specific needs of the intended audience that may influence their perspectives on public health messages

❏ Task 2.3: Engage in dialogue to build trust, increase message effectiveness, and address rumors❏ Activity 3: Ensure messages get to intended audiences via preferred channels and trusted voices

❏ Task 3.1: Tailor channel utilization to increase engagement with intended audiences

❏ Task 3.2: Identify and integrate trusted messengers into messaging efforts to increase uptake and effectiveness❏ Activity 4: Design messages using tone and visuals that will resonate with intended audiences

❏ Task 4.1: Increase engagement by using eye-catching visuals and other formatting

❏ Task 4.2: Revise messaging content and tone to increase messaging reach

❏ Task 4.3: Sync message tailoring for maximum effectiveness❏ Activity 5: Regularly evaluate the engagement and impact of PHEPR communication efforts

❏ Task 5.1: Select and execute an evaluation process complementary to organizational goals and capacities

❏ Task 5.2: Link evaluation results to message development and tailoring efforts

Developing, tailoring, and evaluating key messages is essential to increase messaging effectiveness and the likelihood of positive health behavior change.1-3 Key messages are the primary pieces of information that messengers want their audiences to receive, comprehend, remember, and use.4 Tailoring these messages, which involves adapting major message features like the messenger, channel, use of dialogue, content, tone, and visuals, can help strengthen message effectiveness and reach. Formatting these messages requires careful attention to details like history, culture, shared values, empathy, available technology, and the trustworthiness of the cited source. Messaging efforts should also be continually evaluated to assess their reach and impact to inform further tailoring or new message development. Neglecting these actions can result in low engagement and low uptake of messaging or a failure to reach intended audiences. The Tailoring Tool to Increase Message Uptake & Trust can be used to summarize and apply advice from this section.

Activity 1: Draft key messages

The first step of message development is to formulate key messages based on the information needs of the community. See Priority 2 and Priority 3 for more on how to understand the information needs of communities.

Task 1.1: Embrace a basic content format for communicating accurate information in an emergency

During a PHE, health departments need to quickly disseminate accurate information and recommendations to the public. Effective messages often use the following format and approach:

- Introductory statement: This can be a statement of shared concern or a statement of intent or purpose for the message. Generally, cultural competence and empathy should be emphasized.5

- Key Messages: These include 3–5 of the most important takeaway statements. Public health communicators should consider these 5 elements to motivate public action and compliance.6

- What is the action?

- When should the action take place?

- Where and who should act?

- Why should they act?

- Whose advice is being shared?

- Justification: Messages may benefit from including a justification, such as data from reliable sources trusted by the audience, to support the takeaway statements.

- Conclusion: End with a limited number of summarizing statements and include simplified repetition of key messages. Communicators should work to leave time or create other opportunities for questions and discussion if possible.

Task 1.2: Employ specialized approaches to confront rumors

When public health practitioners are responding to existing or anticipated rumors, they need to consider the risks posed by the spread of that specific rumor and the capacity of the health department to respond. For example, an approach called the “truth sandwich” can be an effective way to prevent the unintentional spread of false or misleading claims.7-9 Messages should:

- Start with the truth

- Indicate the lie and avoid amplifying specific language, if possible

- Return to the truth

See the “Truth Sandwich” Sample Script callout box for more details. For more specific guidance on how to craft content to address false or misleading claims, see our Practical Playbook for Addressing Health Rumors.11

“Truth Sandwich” Sample Script

“Disease X,” a term coined by the World Health Organization (WHO), represents a future unknown disease with uncertain characteristics.10 Uncertainty in the early stages of an emerging PHE is common, and rumors can circulate widely in these situations. Here is an example of how the truth sandwich would be used in this situation:

| Truth | We understand there is a lot of public concern related to the emergence of Disease X. What we know right now is that Disease X causes [insert true symptoms]. |

|---|---|

| Lie | There is no evidence that Disease X has caused [insert false claim: eg, infertility] in children or adults. |

| Truth | Disease X causes [insert true symptoms], and we will continue to share information as it becomes available. |

Task 1.3: Consider and apply lessons from existing messaging models

There is a growing body of work related to key message development. Resources like toolkits, vetted talking points, and infographics created by the Public Health Communications Collaborative (PHCC) have served as a framework for many individual and community leaders to draft their messages. Additionally, the Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) program, created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), provides trainings, tools, and resources to help communicators, emergency responders, and leaders of organizations communicate effectively during emergencies.12 Public health messaging should be simple, concise, empathetic, memorable, tailored, and impactful.

Table 1. Message components based on the CERC framework13

| CERC considerations | Application |

|---|---|

| Present a concise message | Avoid jargon, keep it simple, only include relevant information |

| Repeat the main message | Frequently heard messages can help with retention when uncertainty is high |

| Give action steps in positives (when feasible) | Tell people what to do, more than what not to do |

| Create action steps in threes and fours | Short lists are easier to remember |

| Use personal pronouns | Humanize the message with I/we statements |

| Respect people’s fears and perceptions | Recognize emotions, avoid judgement and condescension |

| Give people options | Avoid patronizing or domineering ways to inform decision making |

Health departments may also draw from their own experiences, considering prior successful messages for similar events or pre-scripting messages for later updating and tailoring.

Activity 2: Tailor messages based on understanding of the intended audience

Message development should center around understanding messaging needs from audiences and their preferences for how to receive and meaningfully engage with information. Providing information is not enough, especially in populations distrustful or suspicious of public health officials. Messages should be framed appropriately according to intended audience characteristics and values.14 Furthermore, public health communicators should consider the value of incorporating two-way dialogue, rather than one-way messages with no feedback mechanism, to increase receptiveness, promote trust, facilitate evaluation efforts, and improve effectiveness.1

Task 2.1: Identify intended audiences for messaging

Often, a public health message is directed at the general public, but sometimes health departments want to prioritize messaging toward a specific intended audience. These audiences may be identified based on demand for accurate information, poor reach of existing accurate messaging, dynamics of circulating rumors, unique information delivery needs, or increased risk or vulnerability to the public health emergency at the time. Some audiences may be large and broad (eg, a demographic category at greater risk of severe disease outcomes), small (eg, a specific affected neighborhood), or even a specific individual (eg, a community member with questions). Prior to an emergency, communicators can use past experience, community data, real-time situational awareness (cultivated in Priority 1 and Priority 2), partner expertise (drawn from Priority 3), and community feedback (established in Priority 4) to identify potential intended audiences for key messages.1,11

Task 2.2: Consider specific needs of the intended audience that may influence their perspectives on public health messages

Different intended audiences have varying needs in how best to frame and present messages to ensure the information fits within their values and belief systems. Message developers should review their knowledge of their intended audience as laid out in Priority 1 and reflect on the demographic characteristics, values, and needs of the audience. Then, public health communicators should reframe message content based on that information as well as input from partners.

Here are a few examples1 of how messages may be reframed according to intended audience characteristics:

- Audiences that distrust public health authorities may be more receptive to messages that do not reference public health authorities.

- Resource-strained communities may prefer messages to be accompanied by support to carry out recommended actions, such as providing masks when recommending mask wearing.

- Broad messaging to diverse audiences with variable needs and willingness to adhere to public health measures may benefit from a harm-reduction approach so that individuals can tailor their actions to address their own risk profiles.

- Populations with strong values regarding personal choice and freedoms may respond better to messages that share information to help with health decision making or personal stories about difficult decision making from members of their own community.

- Populations with limited awareness of public health may benefit from regularly engaging with a specific spokesperson or outreach team.

Task 2.3: Engage in dialogue to build trust, increase message effectiveness, and address rumors

Two-way dialogue between messengers and community members can build trust and increase messaging effectiveness. This may involve engaging with the intended audience over the long-term, taking part in feedback sessions, providing dedicated space for responding to specific questions or concerns, or receiving feedback regarding communication activities. Two-way communication is important to improve awareness of public health, facilitate identification of and response to the community’s information needs, conduct social listening to monitor circulating rumors, actively dispel misleading or false content, evaluate receptiveness to messaging, and, overall, increase trust with communities.1

Two-way communication between public health messengers and intended audiences can be conducted in various ways depending on the needs and preferences of community members and health department abilities.15Examples include allowing for Q&A after a town hall, turning on and answering comments on social media posts, or conducting in-person community engagement at events or in third places.1,15,16 When considering engagement in debunking harmful narratives on social media, critically evaluate the time it takes and the possible impact, including the potential to elevate misleading content. Public health communication teams should always engage with community members with a polite, calm, respectful, compassionate, and nonjudgmental demeanor, even if that same attitude is not returned, as bystanders can be sensitive to perceived disrespect toward community members.1

Activity 3: Ensure messages get to intended audiences via preferred channels and trusted voices

Understanding which communication channels and voices will reach and be trusted by your intended audience is essential for a message to be heard and internalized. Options for message channels and engagement of trusted voices may be dependent on the available resources, skills, or leadership support.1

Task 3.1: Tailor channel utilization to increase engagement with intended audiences

Often, intended audiences are more receptive to receiving information from certain communication channels more than others. Some important communication channels include social media platforms, messaging apps like WhatsApp, radio stations, television broadcasts, print media, press releases, email newsletters, flyers, and in-person engagements such as neighborhood events, religious gatherings, and town halls.17 Some audience members may have differing levels of accessibility to receive and understand communications or differing levels of trust for information received through certain channels compared with others. For example, younger generations may be more likely to engage with messaging delivered through social media or memes,1,6 while rural populations may find messaging through the radio or in-person engagements more accessible due to lack of broadband coverage.1,18

These different channels require different messaging approaches, and some channels are more appropriate for certain message content and complexity. For example, to create effective messaging for social media, engaging content often consists of bright colors, adapting content based off existing trends on platforms, use of emotionally engaging content, and other similar “viral” tactics.19,20 The most effective communication channels will not simply expose intended audiences to information but also enhance opportunities to build trust in public health messaging. Public health communicators should consider infrastructure, personal choice, social norms, and economic levels, among other features, as potential factors that influence intended audiences’ choice of communication channels.2 In many cases, communicators will need to use more than one channel to ensure broad visibility.1

Task 3.2: Identify and integrate trusted messengers into messaging efforts to increase uptake and effectiveness

Message developers should review their knowledge of the intended audience, as discussed in Priority 1, reflect on who the trusted messengers are for that audience, and consider what individuals or organizations could deter message uptake. Intended audiences are less likely to be receptive of messengers they view as untrustworthy or inaccurate while they may be more receptive of messengers they perceive as trustworthy according to shared values, history of interaction, reputation, and affiliation.2 For example, intended audiences with low trust in public health may be more receptive to messaging coming from a local non-health-related community leader rather than an official health department spokesperson.1 These secondary messengers should also have a voice in message development and tailoring as circumstances allow to increase message effectiveness. Otherwise, messages may come off as inauthentic. For more information on fostering successful partnerships with secondary messengers (ie, non-health department messengers), see Priority 2.

Activity 4: Design messages using tone and visuals that will resonate with intended audiences

Incorporating the correct tone and visual components of the message is important to increase reach and opportunities for additional spread through secondary messengers. In some cases, this may mean detouring from standard public health language toward approaches with more humor or lighthearted features.21 Innovation, creativity, and risk-taking beyond existing PHEPR communication practices are needed to keep up with a rapidly evolving communication and media landscape and maximize engagement. However, as always, public health communicators should take an issue-specific approach to incorporation of these features to find an appropriate balance for the topic at hand.1

Task 4.1: Increase engagement by using eye-catching visuals and other formatting

Incorporating visuals, particularly for social media or online content, is key to maximizing engagement, including “likes,” comments, and sharing/reposting.19 In general, good practices include the use of bright colors, simplistic graphics, positive imagery, easy-to-read text, visuals of people and locations representative of the intended audience, accessible visuals and audio, and native speaker translation of language, if applicable. On social media, using hashtags in descriptions, presenting interactive content, embracing visuals or audio from social media trends, creating or enhancing a character persona for the speaker, and including movement/video instead of static imagery can all increase intended audience engagement.20,22 When making decisions on how best to incorporate and utilize visuals, consider the nature of the emergency, the identity of the messenger, the channel used to deliver the message, the intended tone of the message, and the greater cultural, situational, and historical contexts.1,23

Task 4.2: Revise messaging content and tone to increase messaging reach

Intended audiences may engage more with alternative, more creative, or “outside-of-the-box” message content and tone. Examples include messages that use humor or references to current cultural trends (eg, social media platform trends, memes), reference common experiences of the intended audience (eg, use of cultural touchstones or hyperlocal geographic icons), or reframe recommendations based on moral values for issues that have become politicized.1,20,22-24 These types of content changes and tone shifts are best implemented when those with lived experience similar to the intended audience (eg, outside partners who are a part of and serve that intended audience) are leading message tailoring or able to provide input and feedback. Otherwise, this kind of tailoring could backfire23 and risks being perceived as insensitive, inappropriate, or even offensive. See Priority 1 and Priority 2 for more information on recruiting individuals to help with this type of tailoring.

When done correctly, tailoring can make it more likely that intended audiences will engage with the message and even share the message within their own peer or family groups, expanding message reach. Furthermore, social media content of a humorous or emotional nature is more likely to be promoted and viewed on feeds,25 and social media algorithms are more likely to promote demographically tailored and/or trendy content to intended audience viewers.1,20,22

Task 4.3: Sync message tailoring for maximum effectiveness

After determining the most appropriate and effective tailoring for the messenger, channel, use of dialogue, visuals and other formatting, and message content and tone, it is important that communication teams ensure that each piece complements others appropriately. Message tailoring efforts should be synced while keeping in mind the nature of the emergency, intended audience values, the information being conveyed, and cultural, situational, and historical contexts. It is recommended that syncing efforts be done in conjunction with input from or evaluation by individuals with lived experience similar to the intended audience (eg, staff members local to the area, CBOs that serve the intended audience).1

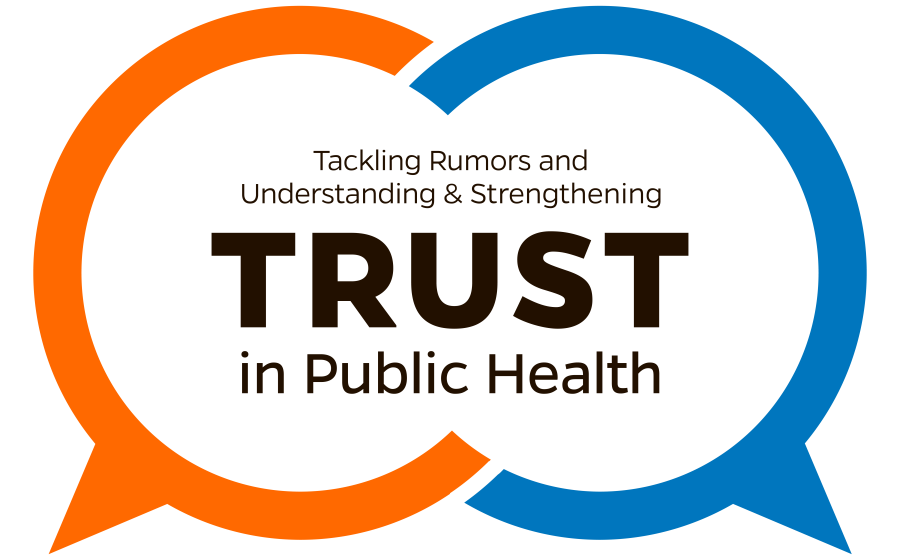

For example, by following the V.I.R.A.L. mnemonic depicted below, social media videos communicating preventative health behaviors may be best tailored with humorous tones, use of positive imagery, and incorporation of social media trends.1,20

Figure 1. V.I.R.A.L. mnemonic for social media engagement strategies in infectious diseases, adapted from Langford BJ et al.20

However, other messages or other channels may be best paired with different types of tailoring. For example, in-person engagement with populations distrustful of public health may be better accepted if they address concerns via dialogue with a calm, neutral, empathetic tone rather than using humor, which would be inappropriate in this setting.

Activity 5: Regularly evaluate the engagement and impact of PHEPR communication efforts

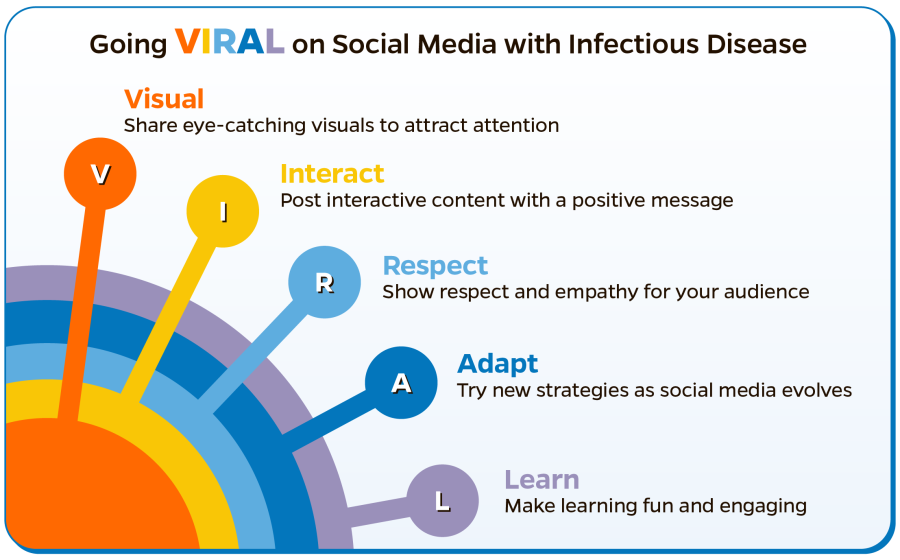

Determining whether messaging influences successful behavior change is difficult to evaluate, but various methods can help health departments assess and adjust their PHEPR communication activities.26-28 These methods should be built into the cycle of developing and disseminating PHEPR content to help tailor messages, reach intended audiences, and increase messaging effectiveness.11 Ideally, messages should be evaluated before and after being shared, as shown in the figure below.1

Figure 2. Message evaluation cycle

Task 5.1: Select and execute an evaluation process complementary to organizational goals and capacities

It can be difficult to determine the direct or indirect impacts that risk communication activities have on health-related behavior change.29-32 Health departments can use a variety of evaluation processes, summarized in the table below, to estimate public health messaging impacts. Evaluation methods can focus on engagement with or awareness of information, attitudes related to health threats, or health-related behaviors or actions.1-3,26,33 They can use qualitative analysis (eg, focus groups, community advisory board feedback), quantitative analysis (eg, factor analysis, meta-regression), or mixed-methods approaches.34 Notably, evaluation efforts should always be informed, and may be limited, by organizational capacities and resources as well as response needs.

Table 2. Examples of PHEPR messaging evaluation methods and metrics

| Communication area being evaluated | Examples of evaluation methods or metrics |

|---|---|

| Awareness of/engagement with public health messaging | Social media engagement statistics (eg, views, likes, shares, comments); webpage views; pre/post calls to information lines; pre/post attendance of health department events; content analysis of feedback submitted via health department social media messaging, email, or phone |

| Awareness of/engagement with misleading claims | Social media content analysis, including engagement statistics (eg, views, likes, shares, comments); topic and volume of questions related to misleading claims |

| Accurate health knowledge and/or belief in rumors | Pre/post messaging campaign survey, focus group, social media content analysis |

| Risk perception of health threat | Survey, focus group, social media content analysis |

| Self-efficacy regarding health behaviors | Survey, focus group, social media content analysis |

| Behavior changes in response to health messaging | Comparison of self-reported behavior change of those exposed to messaging and those not exposed to messaging via survey or social media content analysis, pre/post campaign rate of health services use statistics |

Task 5.2: Link evaluation results to message development and tailoring efforts

By using one or more of the evaluation methods above, health departments will better understand the factors that make their messages more effective or increase message uptake. These may include: messenger; channel(s) used; inclusion of dialogue; message components, including tone, visuals, or other formatting; delivery timing and frequency, especially compared to the greater context of the emergency and public concerns; and usage of concurrent messages with different tailoring.1-3,33,35 PHEPR communication teams can use their findings to adjust the next round of message development or tailoring to maximize its future effectiveness.

Priority 5 References

References

- Potter CM, Grégoire V, Nagar A, et al. A practitioner-focused checklist to build trust, address misinformation and improve risk communication for public health emergencies. [Manuscript submitted for publication.]

- Seeger MW, Pechta LE, Price SM, et al. A Conceptual Model for Evaluating Emergency Risk Communication in Public Health. Health Security. 2018;16(3):193-203. doi:10.1089/hs.2018.0020

- Kreps GL. Epilogue: lessons learned about evaluating health communication programs. J Health Commun. 2014;19(12):1510-1514. doi:10.1080/10810730.2014.954085

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Communication Playbook. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. May 15, 2025. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/103379

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Communicating in a Crisis: Risk Communication Guidelines for Public Officials Communicating in a Crisis. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2019. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-HE20-PURL-gpo144490/pdf/GOVPUB-HE20-PURL-gpo144490.pdf

- Schoch-Spana M, Brunson E, Chandler H, et al. Recommendations on How to Manage Anticipated Communication Dilemmas Involving Medical Countermeasures in an Emergency. Public Health Rep. May 30, 2018. doi:10.1177/0033354918773069

- Tulin M, Hameleers M, de Vreese C, Opgenhaffen M, Wouters F. Beyond Belief Correction: Effects of the Truth Sandwich on Perceptions of Fact-Checkers and Verification Intentions. Journal Pract. February 2, 2024. doi:10.1080/17512786.2024.2311311

- George Lakoff. “Truth Sandwich: 1. Start with the truth. The first frame gets the advantage. 2. Indicate the lie. Avoid amplifying the specific language if possible. 3. Return to the truth. Always repeat truths more than lies. Hear more in Ep 14 of FrameLab w/@gilduran76” December 1, 2018. https://twitter.com/georgelakoff/status/1068891959882846208?lang=en

- Apperson, M. What is a “truth sandwich”? PBS Standards. Updated June 17, 2022. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/standards/blogs/standards-articles/what-is-a-truth-sandwich/

- Tam TWS. Preparing for uncertainty during public health emergencies: What Canadian health leaders can do now to optimize future emergency response. Healthc Manage Forum. March 31, 2020. doi:10.1177/0840470420917172

- Nagar A, Grégoire V, Sundelson A, O’Donnell-Pazderka E, Jamison AM, Sell TK. Practical Playbook for Addressing Health Rumors. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; 2024.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Emergency Preparedness and Response: Manual and Tools. Updated January 23, 2018. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/resources/index.asp

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Crisis & Emergency Risk Communication (CERC): Home. Updated January 23, 2018. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/index.asp

- Public Health Communications Collaborative. Plain Language for Public Health. Public Health Communications Collaborative; 2023. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://publichealthcollaborative.org/wp-content/ uploads/2023/02/PHCC_Plain-Language-for-Public-Health.pdf

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication Manual: Community Engagement. Updated 2018. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/ppt/CERC_CommunityEngagement.pdf

- Diaz SMB and C. “Third places” as community builders. Brookings. Published September 14, 2016. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2016/09/14/third-places-as-community-builders/

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication Manual: Messages and Audiences. Updated 2018. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/ppt/CERC_Messages_and_Audiences.pdf

- Early J, Hernandez A. Digital Disenfranchisement and COVID-19: Broadband Internet Access as a Social Determinant of Health. Health Promot Pract. May 6, 2021. doi:10.1177/15248399211014490

- Ibrahim AM, Lillemoe KD, Klingensmith ME, Dimick JB. Visual Abstracts to Disseminate Research on Social Media: A Prospective, Case-control Crossover Study. Ann Surg. 2017;266(6):e46-e48. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002277

- Langford BJ, Laguio-Vila M, Gauthier TP, Shah A. Go V.I.R.A.L.: Social Media Engagement Strategies in Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. May 15, 2022. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac051

- Boston University School of Public Health. Phrasing and Word Choice. Undated. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://www.bu.edu/sph/students/student-services/student-resources/academic-support/communication-resources/phrasing-and-word-choice/

- Kim HS. Attracting Views and Going Viral: How Message Features and News-Sharing Channels Affect Health News Diffusion. J Commun. May 14, 2015. doi:10.1111/jcom.12160

- Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, Freed GL. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. March 3, 2014. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2365

- Basch CH, Fera J, Pierce I, Basch CE. Promoting Mask Use on TikTok: Descriptive, Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(2):e26392. doi:10.2196/26392

- Kaplan JT, Vaccaro A, Henning M, Christov-Moore L. Moral reframing of messages about mask-wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):10140. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-37075-3

- Ghahramani A, de Courten M, Prokofieva M. The potential of social media in health promotion beyond creating awareness: an integrative review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2402. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-14885-0

- Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321(7262):694-696. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694

- Reynolds B, Seeger MW. Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication as an Integrative Model. J Health Commun. 2005;10(1):43-55. doi:10.1080/10810730590904571

- Blanchard-Coehm RD. Understanding Public Response to Increased Risk from Natural Hazards: Application of the Hazards Risk Communication Framework. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 1998;16(3):247-278. doi:10.1177/028072709801600302

- Heydari ST, Zarei L, Sadati AK, et al. The effect of risk communication on preventive and protective behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: mediating role of risk perception. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):54. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-10125-5

- Bish A, Michie S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. Br J Health Psychol. January 28, 2010. doi:10.1348/135910710X485826

- Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: the need for guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(2):101-102. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-202869

- Dickmann P, McClelland A, Gamhewage GM, de Souza PP, Apfel F. Making sense of communication interventions in public health emergencies – an evaluation framework for risk communication. J Commun Healthc. December 11, 2015. doi:10.1080/17538068.2015.1101962

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluating Communication Campaigns. Public Health Matters Blog. Published April 2, 2018. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://blogs.cdc.gov/ publichealthmatters/2018/04/evaluating-campaigns/. Original source removed.

- Michie S, West R, Sheals K, Godinho CA. Evaluating the effectiveness of behavior change techniques in health-related behavior: a scoping review of methods used. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8(2):212-224. doi:10.1093/tbm/ibx019