Understanding common rumors that emerge during public health emergencies

There are many reasons why misleading rumors spread during public health emergencies (PHEs). Sometimes, people may misinterpret information due to cognitive biases, be influenced by their social, cultural, and political motivations, or simply misunderstand scientific guidance.

While it may appear that unique rumors surface all the time, they often follow clear patterns. By understanding the expected types of rumors, public health communicators can better anticipate and prepare for them.

To understand rumors’ patterns and themes, the TRUST in Public Health team at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security conducted an analysis of 622 of the most widely spread rumors that emerged during select past PHEs, spanning infectious diseases, natural disasters, and other crises like the opioid epidemic.

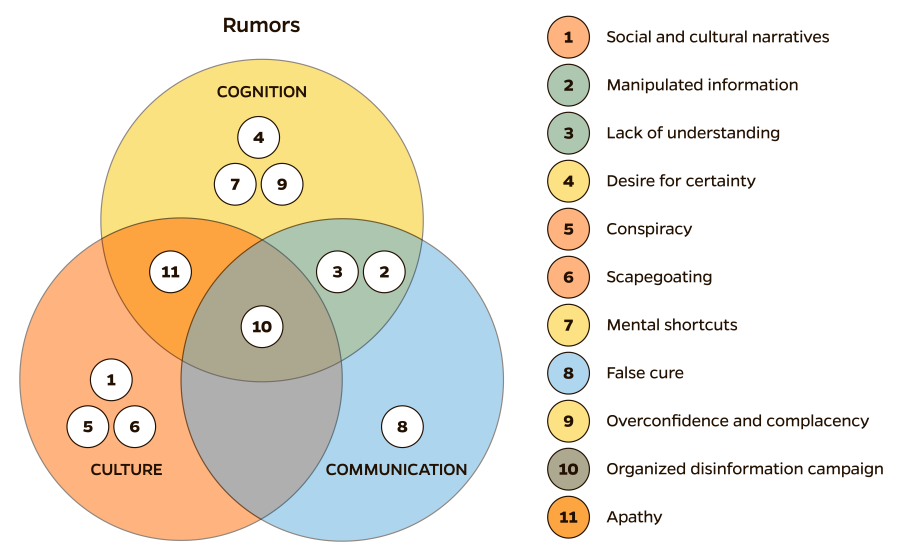

3Cs: Culture, Communication, and Cognition

The analysis showed that rumors during select past PHEs seemed to fall into 3 overarching and overlapping categories: culture, communication, and cognition.

- Culture: Rumors rooted in social, political, and cultural beliefs and practices. This could include beliefs about vaccines being harmful, the government not being trustworthy, some political parties or groups being better/worse than others, and more. This category of rumors can sometimes recycle existing harmful narratives and link them to new public health issues.

- Communication: Rumors that spread because of issues with how accurately and effectively information is shared. This can occur because of poorly framed messages, constantly changing messages, or people misrepresenting issues by misleading, downplaying, inflating, and handpicking information.

- Cognition: Rumors that result from how people think, process new information, and use mental shortcuts to make sense of things they see or experience. This may occur when people interpret information during a crisis. People may jump to conclusions when trying to clarify uncertainty and reduce uncertain risk; stay silent because they believe that most people hold a different opinion from their own; think that other people are more easily influenced than them; interpret information in a way that confirms what they already believe; and feel apathetic or overconfident when experiencing an escalating public health crisis.

Figure 1. Depiction of the 3 overarching and overlapping categories of rumors that emerged during select past PHEs, as well as category-specific themes identified through a content analysis.

Rumor Themes and Subthemes

The analysis found that rumors fit into 11 recurring themes and 31 subthemes. These are:

- Social and cultural narratives: Rumors that leverage personal beliefs driven by social, cultural, and political influences, and personal beliefs and practices that may be slow to change.

- Vaccines: Personal, social, or cultural beliefs related to vaccines, particularly hostility toward and/or fear of them.

- Government distrust: Lack of trust in and skepticism related to government entities and their roles during PHEs.

- Politics: Rumors informed by partisan politics, policies, and/or prominent political figures.

- Sexual and reproductive health: Beliefs that allude to impacts on sexual and reproductive health, particularly fertility.

- Xenophobia: Beliefs often driven by prejudice against or fear of people from outside the US, including immigration-related issues.

- Manipulated information: Rumors that downplay, exaggerate, or distort information about the cause of a disease or PHE, its serious effects, individuals’ sense of security, and other key aspects.

- Chain of events: How a disease or substance passes from person to person or how events happen.

- Deaths: The burden, process, and discourse surrounding deaths related to an emergency.

- Other impacts: The burden, process, severity, and discourse related to other physically and mentally impactful issues in the wake of an emergency.

- Side effects and safety of interventions: Unintended or unforeseen secondary impacts of a PHE or its response and countermeasures.

- Attribution: The actors who receive credit, are implicated, or are seen as responsible during a PHE.

- Affected populations: Groups of people who are impacted by a PHE.

- Symptoms: The effects and manifestations of an emergency on people; for natural disasters, this includes the characteristics of the event.

- Lack of understanding: Rumors that result from issues related to how public health messages are framed, communicated, or continually changed.

- Confusion and bias: When public health sources, government and public-facing agencies, academics, leaders, and other groups or individuals share accurate information about a PHE, but people misinterpret and misrepresent it due to confusion or bias.

- Miscommunication from officials: When official sources and other stakeholders communicate incorrect information about or misrepresent a PHE.

- Desire for certainty: Rumors driven by the need to reduce uncertainty and diminish risk during times of uncertainty. People want to know what will happen, not what might happen, and inaccurate or incorrect narratives may result from seeking certainty.

- Response: Actions taken after an emergency declaration to prevent, mitigate, or adapt to impacts.

- Personal risk: Individual risk of being affected by emergencies involving a disease, substance, or event, or the responses to them.

- Event description: Characteristics of a disease, substance, event, or vector, including its biological, chemical, or meteorological makeup and properties.

- Efficacy: The extent to which responses and mitigation measures achieve the desired or intended results.

- Long-term effects: Effects of an emergency that may occur many months or years later.

- Conspiracy: Rumors driven by unfounded beliefs in deceptive plots, secret/unknown processes, and otherwise difficult-to-prove, unrelated schemes.

- Origin: Theories about the source or origin of a disease, event, or issue.

- Key players: Theories about the role of prominent individuals, leaders, and organizations.

- Public health measures: Theories about responses to a PHE, including mitigation measures, medical countermeasures, or innovative technologies.

- Funding: Theories about financial contributions and gains related to a PHE, such as financing countermeasures or profiteering.

- Scapegoating: Rumors that seek to pin and misdirect blame to others.

- Group: Blaming racial and/or ethnic groups, organizations, countries, or other large categories of people.

- Individual: Blaming specific people.

- Public or government agency: Blaming government, including its agencies, affiliates, officials, or other public entities perceived as duty bearers.

- Businesses: Blaming corporate entities.

- Healthcare personnel: Blaming healthcare workers and other medical professionals.

- Mental shortcuts: Rumors that result from people making biased judgements or jumping to conclusions based on handpicked information or a generally limited understanding of an evolving situation.

- False cure: Rumors of a cure or unapproved intervention that lacks evidence of effectiveness, sought by individuals to avoid standard, conventional, or thoroughly researched treatments.

- Overconfidence and complacency: Rumors arising from people ignoring or dismissing scientific evidence, risks, long-term impacts, or information, often due to or perpetuating a normalcy bias.

- Minimal outcomes: Confidence that a PHE will have minimal or less-than-expected impacts.

- Low risk: Confidence that individuals or communities have minimal or lower-than-anticipated risk.

- Immunity: Confidence that someone is immune to the impacts of a PHE.

- Organized manipulated narratives campaign: Purposefully manipulated narratives driven by a specific person or entity, often with a history of spreading malicious rumors or conspiracy theories.

- Apathy: Rumors arising from a lack of interest or a psychological defense mechanism.

New types of rumors will emerge as public discourse, values, scientific evidence, and the circumstances underlying a PHE change, but public health communicators can look out for these types of rumors to emerge during future emergencies. They can proactively prepare to address them through prebunking and inoculation activities or other culture-, communication-, or cognition-specific actions discussed in Addressing misleading rumors and false narratives based on rumor type.

This research has been submitted to the Journal of Health Communications and is under review.