Addressing misleading rumors and false narratives based on rumor type

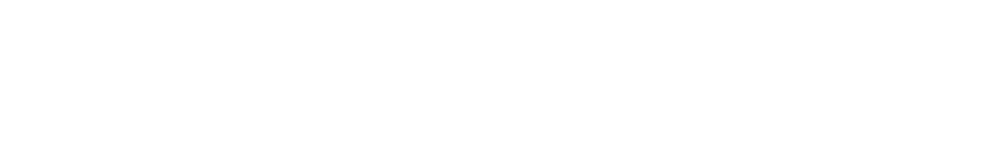

Rumors tend to fall into 3 overarching and overlapping categories: culture, communication, and cognition (“the 3 Cs”). There is no one approach that will successfully reduce all rumor types, so a combination of efforts is typically needed.

Below is a list of actions that can be used to address culture-, communication-, and cognition-related rumors. Actions at the top of each list need fewer resources, while actions at the bottom of the list need more resources. Each situation likely will require different action(s).

Note: Some types of rumors have appeared often during past public health emergencies and could come up again in future events. Learn more about these types of rumor here.

List of actions that can be used to address rumors

Culture-related rumors

Culture-related rumors include those based on social, political, and cultural beliefs and practices. This could look like beliefs about vaccines being harmful, the government not being trustworthy, some political parties or groups being better or worse than others, and more. This category of rumors can sometimes recycle existing harmful narratives and link them to new public health issues.

Actions to address culture-related rumors:

- Moral reframing: use techniques to frame messages in a way that aligns with audience values and beliefs.

- Debunking: refute or correct false claims, especially by explaining the misleading techniques, flawed reasoning, or logical fallacies (ie, logic-based debunking) or by drawing attention to its unreliable source (ie, source-based debunking).

- Partner with trusted, matched messengers: share accurate messages through messengers who represent the audience’s demographics, worldviews, values, and beliefs, and who intended audiences trust and/or listen to.

- Engage communities: unite people behind a shared purpose and solve problems together.

- Build trust: focus on repairing relationships and building trust with communities both before and during public health events.

- Shift social norms: change the unspoken rules that guide people’s behavior and empower people to change how they think/behave.

Tips for improving the effectiveness of actions and avoiding negative consequences:

| DO | DON’T |

|---|---|

|

|

Communication-related rumors

Communication-related rumors include those that spread because of issues with how accurately and effectively information is shared with people. This could be because of poorly framed messages, constantly changing messages, or misrepresenting issues by misleading, downplaying, inflating, and cherry-picking information, either accidentally or intentionally (often done by bad actors who want to take advantage of the public’s negative emotional reaction).

Actions to address communication-related rumors:

- Risk communication: train public health communicators to use good practices when addressing health risks and misleading rumors or false narratives.

- Fill information voids: quickly provide easy-to-understand, credible, accessible, and correct information to people.

- Amplify accurate information: share accessible, audience-specific, and culturally appropriate information from first-hand or other trusted sources or point people to those trusted sources.

- Debunking: refute and fact-check false narratives by pointing out why a claim is false and sharing alternative explanations.

- Improve health, science, and media literacy: teach people to think critically about information, especially how to look for credible information and understand the scientific process.

Tips for improving the effectiveness of actions and avoiding negative consequences:

| DO | DON’T |

|---|---|

|

|

Cognition-related rumors

Cognition-related rumors refers to those that result from how people think, process new information, and use mental shortcuts to make sense of things they see, hear, or experience. This might occur when people process and interpret information during a crisis. People may jump to conclusions when trying to clarify uncertainty and reduce uncertain risk; stay silent because they believe that most people hold a different opinion from their own (pluralistic ignorance); think that other people are more easily influenced than them (third person effect); interpret information in a way that confirms what they already believe (confirmation bias); and feel apathetic or overconfident when experiencing an escalating public health crisis.

Actions to address cognition-related rumors:

- Fill information voids in a simple way: present people with information that requires them to carry out only simple mental tasks to process the information.

- Acknowledge uncertainty: in situations where evidence is evolving, provide information about what you know, what you don’t know, and talk about what the scientific community is trying to learn.

- Provide alternative explanations: “unstick” rumors from people’s minds by showing them alternatives to false claims and encouraging them to think critically about information.

- Reuse people’s cognitive processes: use common cognitive processes and heuristics, or the mental shortcuts people use to understand the world, when creating debunking messages.

- Improve science literacy: teach people to understand how and why public health guidance evolves during health events and teach them to watch for logical fallacies that may mislead them.

Tips for improving the effectiveness of actions and avoiding negative consequences:

| DO | DON’T |

|---|---|

|

|

Please note: The information provided in this section is designed to provide an overview of existing tools and approaches to manage misleading rumors and enhance communication in an environment of mistrust. Determining which tools and approaches are best for specific situations requires a customized approach, as highlighted in the Practical Playbook for Addressing Health Rumors.

References

Click to expand references

- Feinberg M, Willer R. Moral reframing: A technique for effective and persuasive communication across political divides. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2019;13(12):e12501. doi:10.1111/spc3.12501

- Wolsko C, Ariceaga H, Seiden J. Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2016;65:7-19. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2016.02.005

- Feinberg M, Willer R. The Moral Roots of Environmental Attitudes. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(1):56-62. doi:10.1177/0956797612449177

- Lewandowsky S, Cook J. The Conspiracy Theory Handbook. DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln; 2020. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scholcom/246

- Ecker UKH, Lewandowsky S, Cook J, et al. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat Rev Psychol. 2022;1(1):13-29. doi:10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

- Walter N, Murphy ST. How to unring the bell: A meta-analytic approach to correction of misinformation. Commun Monog. 2018;85(3):423-441. doi:10.1080/03637751.2018.1467564

- Whitehead HS, French CE, Caldwell DM, Letley L, Mounier-Jack S. A systematic review of communication interventions for countering vaccine misinformation. Vaccine. 2023;41(5):1018-1034. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.12.059

- Zembylas M. Moving beyond debunking conspiracy theories from a narrow epistemic lens: ethical and political implications for education. Pedago Cult Soc. 2023;31(4):741-756. doi:10.1080/14681366.2021.1948911

- UNICEF Middle East and North Africa, Public Goods Project, First Draft, Yale Institute for Global Health. Vaccine Misinformation Management Field Guide. UNICEF; 2020. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.unicef.org/mena/reports/vaccine-misinformation-management-field-guide

- Lewandowsky S, Ecker UKH, Seifert CM, Schwarz N, Cook J. Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2012;13(3):106-131. doi:10.1177/1529100612451018

- Sutton J, Fischer L, Wood MM. Tornado Warning Guidance and Graphics: Implications of the Inclusion of Protective Action Information on Perceptions and Efficacy. Weather Clim Soc. 2021;13(4):1003-1014. doi:10.1175/WCAS-D-21-0097.1

- Walter N, Tukachinsky R. A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Continued Influence of Misinformation in the Face of Correction: How Powerful Is It, Why Does It Happen, and How to Stop It? Commun Res. 2019;47(2). doi:doi.org/10.1177/0093650219854600

- Shane T. The psychology of misinformation: Why we’re vulnerable. First Draft. Published June 30, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://firstdraftnews.org/articles/the-psychology-of-misinformation-why-were-vulnerable/

- Pennycook G. A Perspective on the Theoretical Foundation of Dual Process Models. In: De Neys W, Ed. Dual Process Theory 2.0. Routledge; 2018.

- Nisbet EC, Kamenchuk O. The Psychology of State-Sponsored Disinformation Campaigns and Implications for Public Diplomacy. Hague J Dipl. 2019;14(1-2):65-82. doi:10.1163/1871191X-11411019

- Walter N, Brooks JJ, Saucier CJ, Suresh S. Evaluating the Impact of Attempts to Correct Health Misinformation on Social Media: A Meta-Analysis. Health Commun. 2021;36(13):1776-1784. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1794553

- Metzger MJ, Flanagin AJ. Credibility and trust of information in online environments: The use of cognitive heuristics. J Pragmat. 2013;59:210-220. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2013.07.012

- Higgins G, Freedman J. Improving decision making in crisis. J Bus Contin Emerg Plan. 2013;7(1):65-76.

- Cummings L. The “Trust” Heuristic: Arguments from Authority in Public Health. Health Commun. 2014;29(10):1043-1056. doi:10.1080/10410236.2013.831685

- Hodson J, Reid D, Veletsianos G, Houlden S, Thompson C. Heuristic responses to pandemic uncertainty: Practicable communication strategies of “reasoned transparency” to aid public reception of changing science. Public Underst Sci. 2023;32(4):428-441. doi:10.1177/09636625221135425

- Chan MS, Jones CR, Jamieson KH, Albarracín D. Debunking: A Meta-Analysis of the Psychological Efficacy of Messages Countering Misinformation. Psychol Sci. 2017;28(11):1531-1546. doi:10.1177/0956797617714579

- Rogers LS, Moran N. Consultation with Nick Moran, Director of Audience Engagement, and Lindsay Smith Rogers, MA, Director of Content Strategy at Communications and Marketing at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Published online October 26, 2023.

- Felgendreff L, Korn L, Sprengholz P, Eitze S, Siegers R, Betsch C. Risk information alone is not sufficient to reduce optimistic bias. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(5):1026-1027. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.01.010

- McColl K, Debin M, Souty C, et al. Are People Optimistically Biased about the Risk of COVID-19 Infection? Lessons from the First Wave of the Pandemic in Europe. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):436. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010436

→ Approaches to counter misleading rumors

→ Addressing misleading rumors and false narratives based on rumor type

→ Practical Playbook for Addressing Health Rumors